Your cart is currently empty!

Category: plsql

-

Khóa học miễn phí PL/SQL – Arrays nhận dự án làm có lương

PL/SQL – Arrays

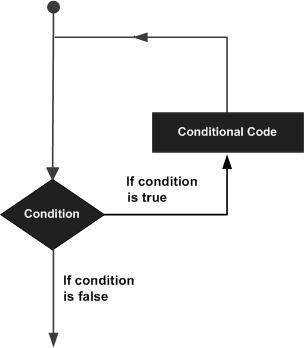

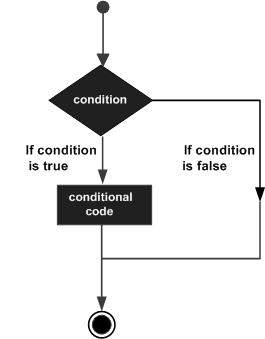

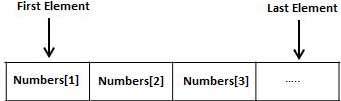

In this chapter, we will discuss arrays in PL/SQL. The PL/SQL programming language provides a data structure called the VARRAY, which can store a fixed-size sequential collection of elements of the same type. A varray is used to store an ordered collection of data, however it is often better to think of an array as a collection of variables of the same type.

All varrays consist of contiguous memory locations. The lowest address corresponds to the first element and the highest address to the last element.

An array is a part of collection type data and it stands for variable-size arrays. We will study other collection types in a later chapter ”PL/SQL Collections”.

Each element in a varray has an index associated with it. It also has a maximum size that can be changed dynamically.

Creating a Varray Type

A varray type is created with the CREATE TYPE statement. You must specify the maximum size and the type of elements stored in the varray.

The basic syntax for creating a VARRAY type at the schema level is −

CREATE OR REPLACE TYPE varray_type_name IS VARRAY(n) of <element_type>

Where,

- varray_type_name is a valid attribute name,

- n is the number of elements (maximum) in the varray,

- element_type is the data type of the elements of the array.

Maximum size of a varray can be changed using the ALTER TYPE statement.

For example,

CREATE Or REPLACE TYPE namearray AS VARRAY(3) OF VARCHAR2(10); / Type created.

The basic syntax for creating a VARRAY type within a PL/SQL block is −

TYPE varray_type_name IS VARRAY(n) of <element_type>

For example −

TYPE namearray IS VARRAY(5) OF VARCHAR2(10); Type grades IS VARRAY(5) OF INTEGER;

Let us now work out on a few examples to understand the concept −

Example 1

The following program illustrates the use of varrays −

DECLARE type namesarray IS VARRAY(5) OF VARCHAR2(10); type grades IS VARRAY(5) OF INTEGER; names namesarray; marks grades; total integer; BEGIN names := namesarray(''Kavita'', ''Pritam'', ''Ayan'', ''Rishav'', ''Aziz''); marks:= grades(98, 97, 78, 87, 92); total := names.count; dbms_output.put_line(''Total ''|| total || '' Students''); FOR i in 1 .. total LOOP dbms_output.put_line(''Student: '' || names(i) || '' Marks: '' || marks(i)); END LOOP; END; /When the above code is executed at the SQL prompt, it produces the following result −

Total 5 Students Student: Kavita Marks: 98 Student: Pritam Marks: 97 Student: Ayan Marks: 78 Student: Rishav Marks: 87 Student: Aziz Marks: 92 PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Please note −

-

In Oracle environment, the starting index for varrays is always 1.

-

You can initialize the varray elements using the constructor method of the varray type, which has the same name as the varray.

-

Varrays are one-dimensional arrays.

-

A varray is automatically NULL when it is declared and must be initialized before its elements can be referenced.

Example 2

Elements of a varray could also be a %ROWTYPE of any database table or %TYPE of any database table field. The following example illustrates the concept.

We will use the CUSTOMERS table stored in our database as −

Select * from customers; +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+ | ID | NAME | AGE | ADDRESS | SALARY | +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+ | 1 | Ramesh | 32 | Ahmedabad | 2000.00 | | 2 | Khilan | 25 | Delhi | 1500.00 | | 3 | kaushik | 23 | Kota | 2000.00 | | 4 | Chaitali | 25 | Mumbai | 6500.00 | | 5 | Hardik | 27 | Bhopal | 8500.00 | | 6 | Komal | 22 | MP | 4500.00 | +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+

Following example makes the use of cursor, which you will study in detail in a separate chapter.

DECLARE CURSOR c_customers is SELECT name FROM customers; type c_list is varray (6) of customers.name%type; name_list c_list := c_list(); counter integer :=0; BEGIN FOR n IN c_customers LOOP counter := counter + 1; name_list.extend; name_list(counter) := n.name; dbms_output.put_line(''Customer(''||counter ||''):''||name_list(counter)); END LOOP; END; /When the above code is executed at the SQL prompt, it produces the following result −

Customer(1): Ramesh Customer(2): Khilan Customer(3): kaushik Customer(4): Chaitali Customer(5): Hardik Customer(6): Komal PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Khóa học lập trình tại Toidayhoc vừa học vừa làm dự án vừa nhận lương: Khóa học lập trình nhận lương tại trung tâm Toidayhoc

Khóa học miễn phí PL/SQL – Cursors nhận dự án làm có lương

PL/SQL – Cursors

In this chapter, we will discuss the cursors in PL/SQL. Oracle creates a memory area, known as the context area, for processing an SQL statement, which contains all the information needed for processing the statement; for example, the number of rows processed, etc.

A cursor is a pointer to this context area. PL/SQL controls the context area through a cursor. A cursor holds the rows (one or more) returned by a SQL statement. The set of rows the cursor holds is referred to as the active set.

You can name a cursor so that it could be referred to in a program to fetch and process the rows returned by the SQL statement, one at a time. There are two types of cursors −

- Implicit cursors

- Explicit cursors

Implicit Cursors

Implicit cursors are automatically created by Oracle whenever an SQL statement is executed, when there is no explicit cursor for the statement. Programmers cannot control the implicit cursors and the information in it.

Whenever a DML statement (INSERT, UPDATE and DELETE) is issued, an implicit cursor is associated with this statement. For INSERT operations, the cursor holds the data that needs to be inserted. For UPDATE and DELETE operations, the cursor identifies the rows that would be affected.

In PL/SQL, you can refer to the most recent implicit cursor as the SQL cursor, which always has attributes such as %FOUND, %ISOPEN, %NOTFOUND, and %ROWCOUNT. The SQL cursor has additional attributes, %BULK_ROWCOUNT and %BULK_EXCEPTIONS, designed for use with the FORALL statement. The following table provides the description of the most used attributes −

| S.No | Attribute & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 |

%FOUND Returns TRUE if an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement affected one or more rows or a SELECT INTO statement returned one or more rows. Otherwise, it returns FALSE. |

| 2 |

%NOTFOUND The logical opposite of %FOUND. It returns TRUE if an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement affected no rows, or a SELECT INTO statement returned no rows. Otherwise, it returns FALSE. |

| 3 |

%ISOPEN Always returns FALSE for implicit cursors, because Oracle closes the SQL cursor automatically after executing its associated SQL statement. |

| 4 |

%ROWCOUNT Returns the number of rows affected by an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement, or returned by a SELECT INTO statement. |

Any SQL cursor attribute will be accessed as sql%attribute_name as shown below in the example.

Example

We will be using the CUSTOMERS table we had created and used in the previous chapters.

Select * from customers; +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+ | ID | NAME | AGE | ADDRESS | SALARY | +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+ | 1 | Ramesh | 32 | Ahmedabad | 2000.00 | | 2 | Khilan | 25 | Delhi | 1500.00 | | 3 | kaushik | 23 | Kota | 2000.00 | | 4 | Chaitali | 25 | Mumbai | 6500.00 | | 5 | Hardik | 27 | Bhopal | 8500.00 | | 6 | Komal | 22 | MP | 4500.00 | +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+

The following program will update the table and increase the salary of each customer by 500 and use the SQL%ROWCOUNT attribute to determine the number of rows affected −

DECLARE

total_rows number(2);

BEGIN

UPDATE customers

SET salary = salary + 500;

IF sql%notfound THEN

dbms_output.put_line(''no customers selected'');

ELSIF sql%found THEN

total_rows := sql%rowcount;

dbms_output.put_line( total_rows || '' customers selected '');

END IF;

END;

/

When the above code is executed at the SQL prompt, it produces the following result −

6 customers selected PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

If you check the records in customers table, you will find that the rows have been updated −

Select * from customers; +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+ | ID | NAME | AGE | ADDRESS | SALARY | +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+ | 1 | Ramesh | 32 | Ahmedabad | 2500.00 | | 2 | Khilan | 25 | Delhi | 2000.00 | | 3 | kaushik | 23 | Kota | 2500.00 | | 4 | Chaitali | 25 | Mumbai | 7000.00 | | 5 | Hardik | 27 | Bhopal | 9000.00 | | 6 | Komal | 22 | MP | 5000.00 | +----+----------+-----+-----------+----------+

Explicit Cursors

Explicit cursors are programmer-defined cursors for gaining more control over the context area. An explicit cursor should be defined in the declaration section of the PL/SQL Block. It is created on a SELECT Statement which returns more than one row.

The syntax for creating an explicit cursor is −

CURSOR cursor_name IS select_statement;

Working with an explicit cursor includes the following steps −

- Declaring the cursor for initializing the memory

- Opening the cursor for allocating the memory

- Fetching the cursor for retrieving the data

- Closing the cursor to release the allocated memory

Declaring the Cursor

Declaring the cursor defines the cursor with a name and the associated SELECT statement. For example −

CURSOR c_customers IS SELECT id, name, address FROM customers;

Opening the Cursor

Opening the cursor allocates the memory for the cursor and makes it ready for fetching the rows returned by the SQL statement into it. For example, we will open the above defined cursor as follows −

OPEN c_customers;

Fetching the Cursor

Fetching the cursor involves accessing one row at a time. For example, we will fetch rows from the above-opened cursor as follows −

FETCH c_customers INTO c_id, c_name, c_addr;

Closing the Cursor

Closing the cursor means releasing the allocated memory. For example, we will close the above-opened cursor as follows −

CLOSE c_customers;

Example

Following is a complete example to illustrate the concepts of explicit cursors &minua;

DECLARE

c_id customers.id%type;

c_name customers.name%type;

c_addr customers.address%type;

CURSOR c_customers is

SELECT id, name, address FROM customers;

BEGIN

OPEN c_customers;

LOOP

FETCH c_customers into c_id, c_name, c_addr;

EXIT WHEN c_customers%notfound;

dbms_output.put_line(c_id || '' '' || c_name || '' '' || c_addr);

END LOOP;

CLOSE c_customers;

END;

/

When the above code is executed at the SQL prompt, it produces the following result −

1 Ramesh Ahmedabad 2 Khilan Delhi 3 kaushik Kota 4 Chaitali Mumbai 5 Hardik Bhopal 6 Komal MP PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Khóa học lập trình tại Toidayhoc vừa học vừa làm dự án vừa nhận lương: Khóa học lập trình nhận lương tại trung tâm Toidayhoc